Poor medication adherence is a problem that has gone “unsolved” for decades. But combining smart caps with individualized feedback can drive the adherence that proves the investigational product efficacy and underwrites approvals.

In this case study, we set out the crucial role of medication adherence in clinical research and explain how using AARDEX® Group’s Smart Cap, the MEMS® Cap, in a study of Gilead’s Truvada helped inform the FDA’s recommended approach to tackling poor patient adherence in clinical trials, as set out in its Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Determination of Effectiveness of Human Drugs and Biological Products.

The Problem: Why Patient Adherence Matters

While the exact figure varies between therapy areas and development stages, only around 13.8% of products that enter industry-sponsored Phase I trials ever go on to obtain FDA approval.1

It’s a time-consuming and expensive problem, but one that can, at least in part, be modified with a focus on medication adherence.

The leading cause of study failure, according to a 2018 review of the data from the previous 30 years, is an inability to demonstrate efficacy.2 The authors pointed to one analysis of 640 Phase III novel therapeutic trials. More than half, 54%, had failed in clinical development, and, of those, 57% were attributed to inadequate efficacy.3

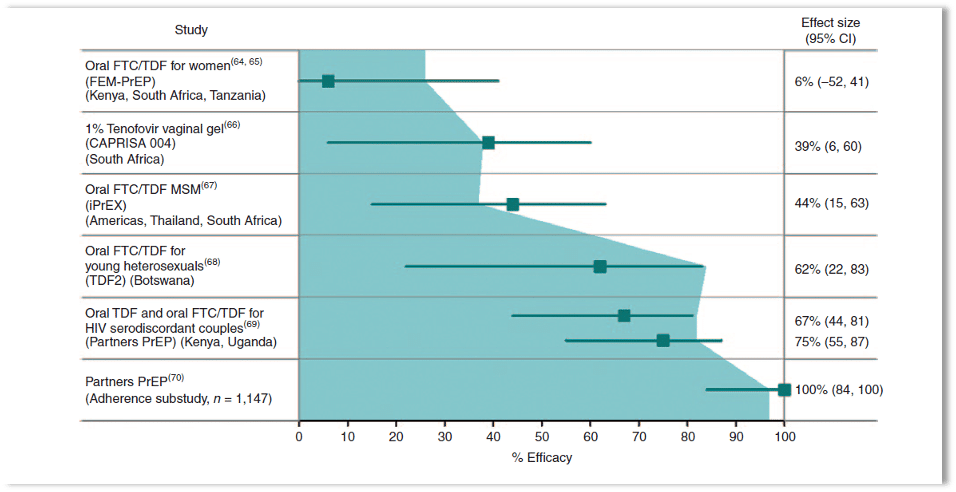

However, this doesn’t necessarily mean the drug is ineffective. As demonstrated by a review of studies in the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) space, lack of efficacy is often directly correlated to poor adherence. (see fig 1).

The Evidence: Adherence-Informed Analysis

Poor medication adherence is a long-standing problem in clinical trials, but, until recently, the industry lacked the tools necessary to tackle it. Instead, sponsors and CROs have been forced to rely on subjective, inaccurate measurements, such as pill counting, self-report, or invasive techniques, such as product levels in blood or urine.

In a 2012 study of oral FTC/TDC for women (FEM-PrEP), for example, adherence measured by self-report was 83%, compared to just 30% when measured by blood concentrations.4

The study returned a statistically insignificant efficacy rate of just 6%, prompting researchers to ask if poor medication adherence, rather than drug formulation, was the problem. A review of trials in similar products, with varying degrees and methods of adherence support, appeared to show a correlation between adherence and efficacy, further supporting the hypothesis.

The Partners PrEP study of Truvada in 1,147 people at a high risk of contracting HIV, used AARDEX® Group’s, MEMS®Cap. The smart cap captured doses being removed from the bottle and MEMS® Adherence Software (MEMS AS®) was used to provide adherence behavior analysis to the study team. Each month, this analysis was fed back to the study participant, and any necessary adherence support was provided.

This approach contributed to an adherence rate of 96% – and an efficacy rate of 100%.5

Figure 1: The relationship between adherence to treatment and efficacy—results from several human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention trials.

Symbols and error bars depict the effect size; the blue area marks the percentage of patients who adhered to the prescribed treatment. CAPRISA, Centre for the AIDS Programme Research in South Africa; CI, confidence interval; FTC, emtricitabine; MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

The Outcome: FDA Recommendations

Speaking during a session at the American Course on Drug Development and Regulatory Sciences (ACDRS) meeting, FDA reviewers of the dossier made several conclusions. They included that self-report and pill count were ineffective adherence measures6 and that is largely in part what helped shape the development of the 2019 enrichment strategies guidance.

The document recognizes that the reliability of patient adherence data should be improved as it provides valuable safety and efficacy information, and that more attention should be paid to adherence data during regulatory review.

It also recommends drug developers decrease heterogeneity by identifying and selecting patients likely to adhere to the protocol-specified dosing regimen, use smart packaging to quantify and monitor drug use and encourage patient adherence.

The Conclusion: Patient Adherence is a Modifiable Risk Factor

No covariate, the FDA reviewers said during the ACDRS meeting, can have a larger impact on study success than not taking the drug.

Granted, there are a plethora of factors that could stop a trial in its tracks, from a shortage of funding for completion to problems related to patient recruitment and enrolment.

But thanks to advances in technology and the advent of smart packaging, poor patient adherence is now a modifiable risk factor. As this review shows, a focus on medicines-taking behavior could give your portfolio the very best chance of success.

References

- Heem Wong, C., Wei Siah, K et al. Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. (2018). https://academic.oup.com/biostatistics/article/20/2/273/4817524

- Fogel, D. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: A review. (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6092479/

- Hwang, T., Carpenter., D., et al. Failure of Investigational Drugs in Late-Stage Clinical Development and Publication of Trial Results. (2016) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27723879/

- Karim, S., Karim, Q., et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis: a defining moment in HIV control. (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3253379/

- Baeten, J., Donnell, D., et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. (2012). https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa1108524

- FDA. Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Approval of Human Drugs and Biological Products: Guidance for Industry. (2019). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/enrichment-strategies-clinical-trials-support-approval-human-drugs-and-biological-products